During this week’s session, taken by Dr Carolyn Peiffer, we examined three broad typologies of corruption within academic literature: specifically principle-agent view, collective action view and a functional view. This session highlighted the normative complexities behind different definitions of corruption. Though an important and interesting discussion, I don’t wish to focus on that aspect in this blog post. But for the sake of clarity, I’ve taken a basic Oxford Dictionary definition of Corruption as ‘dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, typically involving bribery’.

I concur with the idea that there are different ways of explaining corruption (3 of which are mentioned here). Consequently, I find each typology to have its own merits, though I wouldn’t say that any of them are sufficient explanations on their own. For instance a principal-agent view, which focuses more on an individual’s decision on whether or not to engage in corrupt practices, negates wider contextual contributors to corruption at a petty, grassroots level, which a collective action explanation would engage with. After all, as stated by Marquette and Peifer, “When corruption is seen as ‘normal’, people may be less willing to abstain from corruption or to take the first step in implementing sanctions or reforms.” I may be over-stating this, but I don’t know that anyone who has had any kind of exposure to an environment of systemic corruption can disagree with this statement.

However a key theme which (importantly, in my view) emerged from the lecture in examining the different typologies of corruption, was the oft-systemic nature of corruption and the variance in its forms, even within a single society. So you could say that I find the functional theory the most convincing in terms of creating a thought-pathway to progressive change regarding corruption.

Functional Corruption: Perpetrator-Victim fluidity

To be 100% clear, I am in a no way a corruption apologist. However, the reality, which thankfully literature on corruption is beginning to show, is that as Peiffer and Marquette highlight, corruption can serve important problems, solving dilemmas people face especially in weak institutional environments.

Transparency International’s pamphlet “Real lives, True Stories” highlighted various instances of corruption which were often addressed with the help of TI’s intervention. This included cases of doctors and nurses charging additional fees and extorting money from people, in order to grant access urgent healthcare for their children; this included a case-study taken from Morocco. In the case relayed, the perpetrator (the nurse) who had been caught red-handed was arrested and subsequently jailed.

Looking at these cases, I was filled with sadness at what I read, but also questions, the answers for which were not provided. If I understand that corruption can be part of a systemic, widespread problem then a logical concern would be to ask questions about the ways in which the nurse had been subjected to corruption and bad governance so that he had resorted to measures such as extorting money from people over urgent and life threatening medical care, potentially to cover his shortfall. I don’t disagree with bringing perpetrators to justice in these cases. But I also don’t think that we can afford to overlook the nuance or the moral complexity of root causes which must be addressed if anti-corruption schemes are going to be worth it; so it’s pleasing to see a functional view on corruption start to do this work.

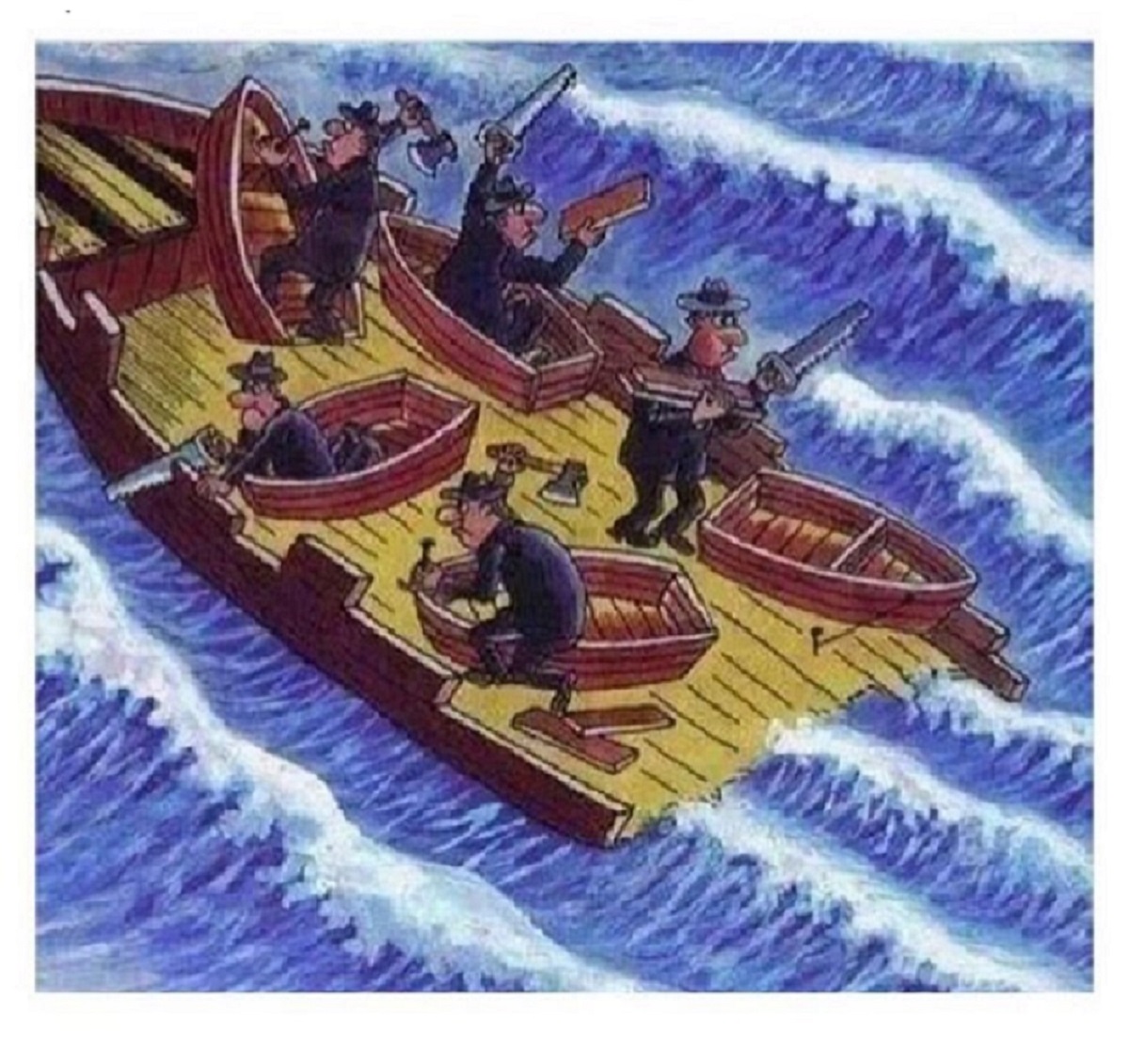

Like with sessions 2 and 3, I feel that the fluidity between the identities of victimisers and victim in the context of corruption is often betrayed because of a particular understanding of social and state-society relations; a nuance which I think, quite cleverly, one of the group exercises this week was designed to highlight to us. In our, very culturally diverse, groups we were given scenarios and asked to rate them separately on whether they were corrupt and whether they were morally wrong. Interestingly, the scores for each criterion per individual scenarios varied greatly when compared within and across groups. I came away from our spirited, lively discussions with the sense that these differences were testament to our different backgrounds and prior experiences with corruption.

So what do we do?

It seems abundantly clear that a linear cause and effect approach to tackling corruption may be hopelessly simplistic and idealistic.

It is important to acknowledge the role played in fueling corruption, by powerful interests, which I think may be the biggest difficulty in dealing with it. One of my class-mates drew attention to the seeming disproportionate focus in the literature on petty corruption and not the huge transactions in which (for example) large powerful multi-national corporations may engage.

I thoroughly agreed with him. But when you have systems that benefit the interests of those who are rarely put under a microscope, what then happens?

I have no more answers, but I guess questions like this are what (development) politics is all about.

Sources

Marquette, H., Peiffer, C. (2015) Corruption and Collective Action Development Leadership Programme.[pdf online] Available here: file:///G:/ID-DevPol/DLP%20-%20Corruption%20and%20Collective%20Action%202015.pdf

Transparency International (2016) Real lives, True Stories. [pdf online]. Available here: file:///G:/ID-DevPol/2014_TrueStoriesBooklet%20(2).pdf